Introducing Container Runtime Interface (CRI) in Kubernetes

Editor’s note: this post is part of a series of in-depth articles on what’s new in Kubernetes 1.5

At the lowest layers of a Kubernetes node is the software that, among other things, starts and stops containers. We call this the “Container Runtime”. The most widely known container runtime is Docker, but it is not alone in this space. In fact, the container runtime space has been rapidly evolving. As part of the effort to make Kubernetes more extensible, we’ve been working on a new plugin API for container runtimes in Kubernetes, called “CRI”.

What is the CRI and why does Kubernetes need it?

Each container runtime has it own strengths, and many users have asked for Kubernetes to support more runtimes. In the Kubernetes 1.5 release, we are proud to introduce the Container Runtime Interface (CRI) – a plugin interface which enables kubelet to use a wide variety of container runtimes, without the need to recompile. CRI consists of a protocol buffers and gRPC API, and libraries, with additional specifications and tools under active development. CRI is being released as Alpha in Kubernetes 1.5.

Supporting interchangeable container runtimes is not a new concept in Kubernetes. In the 1.3 release, we announced the rktnetes project to enable rkt container engine as an alternative to the Docker container runtime. However, both Docker and rkt were integrated directly and deeply into the kubelet source code through an internal and volatile interface. Such an integration process requires a deep understanding of Kubelet internals and incurs significant maintenance overhead to the Kubernetes community. These factors form high barriers to entry for nascent container runtimes. By providing a clearly-defined abstraction layer, we eliminate the barriers and allow developers to focus on building their container runtimes. This is a small, yet important step towards truly enabling pluggable container runtimes and building a healthier ecosystem.

Overview of CRI

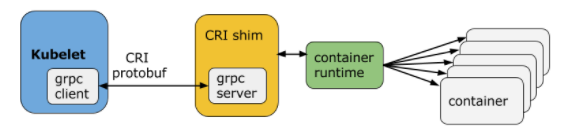

Kubelet communicates with the container runtime (or a CRI shim for the runtime) over Unix sockets using the gRPC framework, where kubelet acts as a client and the CRI shim as the server.

The protocol buffers API includes two gRPC services, ImageService, and RuntimeService. The ImageService provides RPCs to pull an image from a repository, inspect, and remove an image. The RuntimeService contains RPCs to manage the lifecycle of the pods and containers, as well as calls to interact with containers (exec/attach/port-forward). A monolithic container runtime that manages both images and containers (e.g., Docker and rkt) can provide both services simultaneously with a single socket. The sockets can be set in Kubelet by –container-runtime-endpoint and –image-service-endpoint flags.

Pod and container lifecycle management

service RuntimeService {

// Sandbox operations.

rpc RunPodSandbox(RunPodSandboxRequest) returns (RunPodSandboxResponse) {}

rpc StopPodSandbox(StopPodSandboxRequest) returns (StopPodSandboxResponse) {}

rpc RemovePodSandbox(RemovePodSandboxRequest) returns (RemovePodSandboxResponse) {}

rpc PodSandboxStatus(PodSandboxStatusRequest) returns (PodSandboxStatusResponse) {}

rpc ListPodSandbox(ListPodSandboxRequest) returns (ListPodSandboxResponse) {}

// Container operations.

rpc CreateContainer(CreateContainerRequest) returns (CreateContainerResponse) {}

rpc StartContainer(StartContainerRequest) returns (StartContainerResponse) {}

rpc StopContainer(StopContainerRequest) returns (StopContainerResponse) {}

rpc RemoveContainer(RemoveContainerRequest) returns (RemoveContainerResponse) {}

rpc ListContainers(ListContainersRequest) returns (ListContainersResponse) {}

rpc ContainerStatus(ContainerStatusRequest) returns (ContainerStatusResponse) {}

...

}

A Pod is composed of a group of application containers in an isolated environment with resource constraints. In CRI, this environment is called PodSandbox. We intentionally leave some room for the container runtimes to interpret the PodSandbox differently based on how they operate internally. For hypervisor-based runtimes, PodSandbox might represent a virtual machine. For others, such as Docker, it might be Linux namespaces. The PodSandbox must respect the pod resources specifications. In the v1alpha1 API, this is achieved by launching all the processes within the pod-level cgroup that kubelet creates and passes to the runtime.

Before starting a pod, kubelet calls RuntimeService.RunPodSandbox to create the environment. This includes setting up networking for a pod (e.g., allocating an IP). Once the PodSandbox is active, individual containers can be created/started/stopped/removed independently. To delete the pod, kubelet will stop and remove containers before stopping and removing the PodSandbox.

Kubelet is responsible for managing the lifecycles of the containers through the RPCs, exercising the container lifecycles hooks and liveness/readiness checks, while adhering to the restart policy of the pod.

Why an imperative container-centric interface?

Kubernetes has a declarative API with a Pod resource. One possible design we considered was for CRI to reuse the declarative Pod object in its abstraction, giving the container runtime freedom to implement and exercise its own control logic to achieve the desired state. This would have greatly simplified the API and allowed CRI to work with a wider spectrum of runtimes. We discussed this approach early in the design phase and decided against it for several reasons. First, there are many Pod-level features and specific mechanisms (e.g., the crash-loop backoff logic) in kubelet that would be a significant burden for all runtimes to reimplement. Second, and more importantly, the Pod specification was (and is) still evolving rapidly. Many of the new features (e.g., init containers) would not require any changes to the underlying container runtimes, as long as the kubelet manages containers directly. CRI adopts an imperative container-level interface so that runtimes can share these common features for better development velocity. This doesn’t mean we’re deviating from the “level triggered” philosophy - kubelet is responsible for ensuring that the actual state is driven towards the declared state.

Exec/attach/port-forward requests

service RuntimeService {

...

// ExecSync runs a command in a container synchronously.

rpc ExecSync(ExecSyncRequest) returns (ExecSyncResponse) {}

// Exec prepares a streaming endpoint to execute a command in the container.

rpc Exec(ExecRequest) returns (ExecResponse) {}

// Attach prepares a streaming endpoint to attach to a running container.

rpc Attach(AttachRequest) returns (AttachResponse) {}

// PortForward prepares a streaming endpoint to forward ports from a PodSandbox.

rpc PortForward(PortForwardRequest) returns (PortForwardResponse) {}

...

}

Kubernetes provides features (e.g. kubectl exec/attach/port-forward) for users to interact with a pod and the containers in it. Kubelet today supports these features either by invoking the container runtime’s native method calls or by using the tools available on the node (e.g., nsenter and socat). Using tools on the node is not a portable solution because most tools assume the pod is isolated using Linux namespaces. In CRI, we explicitly define these calls in the API to allow runtime-specific implementations.

Another potential issue with the kubelet implementation today is that kubelet handles the connection of all streaming requests, so it can become a bottleneck for the network traffic on the node. When designing CRI, we incorporated this feedback to allow runtimes to eliminate the middleman. The container runtime can start a separate streaming server upon request (and can potentially account the resource usage to the pod!), and return the location of the server to kubelet. Kubelet then returns this information to the Kubernetes API server, which opens a streaming connection directly to the runtime-provided server and connects it to the client.

There are many other aspects of CRI that are not covered in this blog post. Please see the list of design docs and proposals for all the details.

Current status

Although CRI is still in its early stages, there are already several projects under development to integrate container runtimes using CRI. Below are a few examples:

- cri-o: OCI conformant runtimes.

- rktlet: the rkt container runtime.

- frakti: hypervisor-based container runtimes.

- docker CRI shim.

If you are interested in trying these alternative runtimes, you can follow the individual repositories for the latest progress and instructions.

For developers interested in integrating a new container runtime, please see the developer guide for the known limitations and issues of the API. We are actively incorporating feedback from early developers to improve the API. Developers should expect occasional API breaking changes (it is Alpha, after all).

Try the new CRI-Docker integration

Kubelet does not yet use CRI by default, but we are actively working on making this happen. The first step is to re-integrate Docker with kubelet using CRI. In the 1.5 release, we extended kubelet to support CRI, and also added a built-in CRI shim for Docker. This allows kubelet to start the gRPC server on Docker’s behalf. To try out the new kubelet-CRI-Docker integration, you simply have to start the Kubernetes API server with –feature-gates=StreamingProxyRedirects=true to enable the new streaming redirect feature, and then start the kubelet with –experimental-cri=true.

Besides a few missing features, the new integration has consistently passed the main end-to-end tests. We plan to expand the test coverage soon and would like to encourage the community to report any issues to help with the transition.

CRI with Minikube

If you want to try out the new integration, but don’t have the time to spin up a new test cluster in the cloud yet, minikube is a great tool to quickly spin up a local cluster. Before you start, follow the instructions to download and install minikube.

Check the available Kubernetes versions and pick the latest 1.5.x version available. We will use v1.5.0-beta.1 as an example.

$ minikube get-k8s-versionsStart a minikube cluster with the built-in docker CRI integration.

$ minikube start --kubernetes-version=v1.5.0-beta.1 --extra-config=kubelet.EnableCRI=true --network-plugin=kubenet --extra-config=kubelet.PodCIDR=10.180.1.0/24 --iso-url=http://storage.googleapis.com/minikube/iso/buildroot/minikube-v0.0.6.iso

–extra-config=kubelet.EnableCRI=true` turns on the CRI implementation in kubelet. –network-plugin=kubenet and –extra-config=kubelet.PodCIDR=10.180.1.0/24 sets the network plugin to kubenet and ensures a PodCIDR is assigned to the node. Alternatively, you can use the cni plugin which does not rely on the PodCIDR. –iso-url sets an iso image for minikube to launch the node with. The image used in the example

Check the minikube log to check that CRI is enabled.

$ minikube logs | grep EnableCRI I1209 01:48:51.150789 3226 localkube.go:116] Setting EnableCRI to true on kubelet.Create a pod and check its status. You should see a “SandboxReceived” event as a proof that Kubelet is using CRI!

$ kubectl run foo --image=gcr.io/google\_containers/pause-amd64:3.0 deployment "foo" created $ kubectl describe pod foo ... ... From Type Reason Message ... ----------------- ----- --------------- ----------------------------- ...{default-scheduler } Normal Scheduled Successfully assigned foo-141968229-v1op9 to minikube ...{kubelet minikube} Normal SandboxReceived Pod sandbox received, it will be created. ...

_Note that kubectl attach/exec/port-forward does not work with CRI enabled in minikube yet, but this will be addressed in the newer version of minikube. _

Community

CRI is being actively developed and maintained by the Kubernetes SIG-Node community. We’d love to hear feedback from you. To join the community:

-

Post issues or feature requests on GitHub

Join the #sig-node channel on Slack

Subscribe to the SIG-Node mailing list

Follow us on Twitter @Kubernetesio for latest updates

–Yu-Ju Hong, Software Engineer, Google